A team of students from the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University is bringing safe, clean air to communities on the other side of the globe. Climate change has wiped out major food sources for nomadic communities in Mongolia—forcing them to migrate into the congested and polluted city of Ulaanbaatar. According to UNICEF, over the past eleven years, respiratory infections have increased by over 250%, with severe effects on children. The nomadic communities of Ulaanbaatar are experiencing an epidemic of dangerous air quality.

To combat this issue, the Project Koyash team has designed a solar-powered air filtration system that can autonomously clean air qualities of up to 500 AQI (air quality index) within a fraction of an hour. The team’s goal is to filter the air within the homes of these nomadic communities and is working with the nonprofit organization Taiwan Fund for Children and Families (TFCF). EPICS in IEEE has granted the project US$10,000 to continue deploying these systems within the community of Ulaanbaatar. EPICS in IEEE recently sat down with team leader Bryan Yavari and project advisor Shamsher (Shami) Warudkar to get an update about their work.

Yavari starts by telling us a little about the project name, explaining that Koyash is the name of the Mongolian God of the Sun. “We wanted to pay homage to the Mongolian culture and use our project to raise awareness for the area of Ulaanbaatar and their culture.” With one unit already delivered to Mongolia, the team has begun the deployment phase and plans to continue testing the system and manufacturing units, sending 24 total to Ulaanbaatar. The team believes the deployable, fully autonomous filtration system will aid families by providing something they desperately need—clean air.

The project was initiated by Warudkar when he saw the need for these air filters in Mongolia after reading an article in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization. The nomadic communities, not connected to the city’s electrical grid, burn unrefined coal to keep warm. Warudkar explains it is “a choice between staying warm and having breathable air.” In a city already plagued by pollution, he adds, “we at least want to provide them with clean air at home to re-establish homeostasis before they go back to work or into the larger community.”

For the project, the team designed their air-filtration system to be solar-powered since Ulaanbaatar gets, on average, 290 days of sunlight a year. The solar panel goes to a few different components, including a battery, Arduino (microcontroller), an inverter, and an air filter. All the systems are housed in a 3D-printed weatherproof box which protects the system from harsh weather. The system is designed to “run autonomously so that the residents don’t have to turn it off and on or move anything,” noted Yavari.

According to Yavari, one of the project’s biggest successes was “having our system work seamlessly with so many different components while accomplishing the daunting task of purifying the air.” Warudkar credits the system engineering process with helping them work and discover the best solution. “I’m proud that we were able to explore and iterate to eventually come to this solution.”

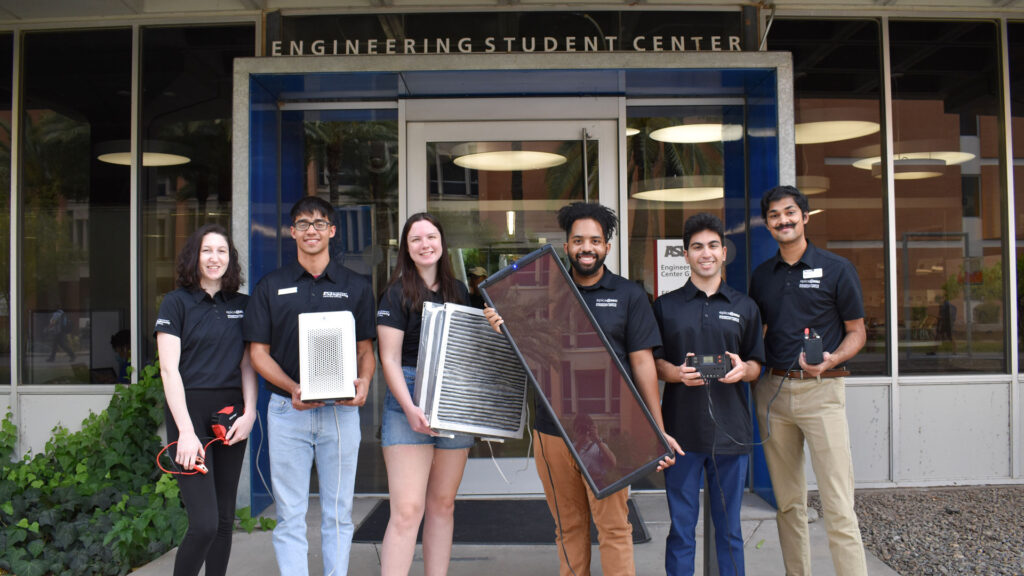

The multi-disciplinary team was also a factor in the ongoing success of Project Koyash. “Our team has been adaptable and passionate about learning other fields,” said Yavari. In addition to Yavari, who is a Neuroscience major, and Warudkar, who was an Aerospace Engineering major before graduating last year, there are six other team members: Jalen Goode, Mechanical Engineering; Oscar Campa, Aerospace Engineering; Sarah Johnston, Mechanical Engineering; Catherine Johnston, Engineering Management; Merin Jacob, Computer Science; Tommy Montero, Aerospace Engineering, and Malone Roark, Industrial Design. “We’ve all learned so much, and we’re all bringing different items and skills to the table,” added Warudkar.

Working with their nonprofit organization, TFCF, has been invaluable, notes Yavari and Warudkar. “There is a big distance between us and Mongolia, so when we started this, one of the first things we needed was boots on the ground,” said Warudkar. TFCF has been very helpful in connecting with the local community, setting up our first prototype, and getting us data. “Without a local partner, we could not do what we’re doing now,” explained Warudkar. In their talks with the Mongolian Consulate at the beginning of the project, it was clear that the people of Mongolia are looking for solutions to this problem—”but there are not many groups trying to find solutions,” added Yavari.

Reflecting on lessons learned during the project, Yavari and Warudkar agreed that patience and adaptability are critical. “Especially when you have an international project, there are going to be lots of roadblocks that no one can anticipate and no one can control,” said Yavari. Adding that, “you must adjust and learn from obstacles to move forward successfully.” Another lesson is to be “willing to put yourself out there,” said Warudkar. “This (project) didn’t just fall in our laps; this was something that we had to deliberately go out there and figure out. When people are at home watching a documentary about how climate change affects the world, they often say, ‘oh man, that sucks, but I can’t do anything about it.’ But when you really put yourself out there and do the work to move forward, you can accomplish so much.” It’s important to keep trying no matter what and “make sure that project is still spearheading forward despite any other outside challenges,” said Yavari

While the project may have started as part of their coursework, it has grown into something more. Project Koyash is now registered as a limited liability company (LLC), which should help the project continue to move forward. As for the next steps, the team hopes to go to Mongolia to set up the system to ensure that the system works properly and educate the community about the technology. The team’s ultimate goal is to develop a local supply chain in Ulaanbaatar; this would allow us to help the more than 80,000 residents in the Ger district.

Recent Comments